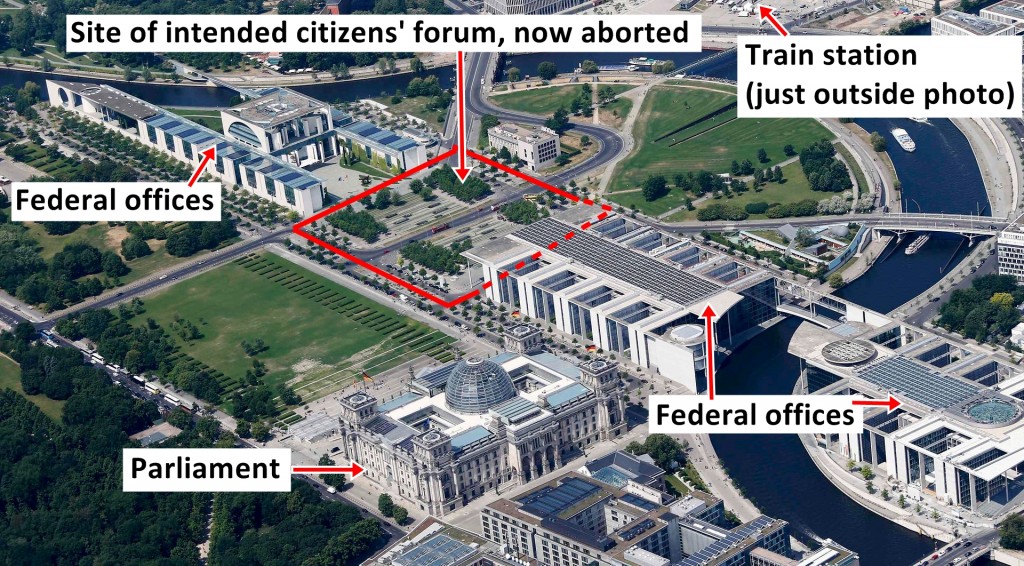

After 26 years of hemming and hawing, the Berlin city council recently decided for good that the central focal point of the federal government district, where a “citizens’ forum” was supposed to be built, will remain a street with car traffic and an empty span of concrete and lawn on either side. The original plans from the time of Germany’s reunification after the fall of the Berlin Wall called for this focal point to have public spaces and facilities where citizens and government would interact, the governed and the governors, a democracy lab.

This is a “new low for city planning in Berlin”, said a former Berlin Planning Commissioner. The media has been unanimous in deploring the decision, calling it a betrayal of the people and abdication of civic duty. I was unable to find even one statement in the media in support of abandoning the forum. I will argue that the decision has the hallmarks of being fuel for hard-right racist populism.