The Dessau-Wörlitz Garden Realm is a breathtaking and absolutely unique series of parks and gardens from around 1770 with villas, pavilions and other structures scattered around these two towns in a remote part of eastern Germany, forming what is probably the world’s intact largest assemblage of neoclassical structures, gardens, and designed landscapes. Further, it was an early progenitor of what we now call environmental education and public access to green space. Sadly, it is little known even by Germans and almost not all outside Germany although the name Dessau is world-renowned as the home of the Bauhaus design school after it moved there from the town of Weimar.

A UNESCO World Heritage site since 2000, the Garden Realm is considered to be one of the earliest and most extensive introductions of Enlightenment thinking, values and neoclassical aesthetics into Germany from their origins in France and England. This seismic shift embraced humanistic reasoning, scholarly curiosity, and open-minded exploration. In terms of art and aesthetics, it marked a shift away from the baroque flamboyance and rococo excess of the 17th and early 18th centuries and towards restrained interpretations of classical Greek and Roman styles.

The Garden Realm was just one of a remarkable range of Enlightenment-related endeavors of the duke of Anhalt-Dessau, Leopold III, more commonly known as Fürst Franz (Prince Franz) or Friedrich Franz. He wanted to bring Enlightenment values and education to the general public, and so the parks were open to the public and included demonstration gardens and farms for agricultural education and research.

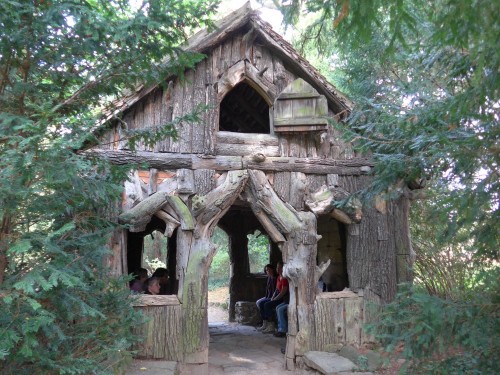

The parks are in the naturalistic, so-called “picturesque” style which was developed in England in the 18th century and broke from the Baroque preference for formal, geometric flower beds, shrubs pruned into precise shapes, and trees lined up in precise allées. This is what you see at your typical palace in Europe and many European parks in general (picture Versailles). Virtually every American knows the English picturesque style, even if they don’t know the name, because that’s the style used in virtually every American city park. We don’t think of it as a “style”; for us it’s just what a park is. The Garden Realm has all the typical English features such as natural-seeming woods and ponds, punctuated by sight axes and a restrained smattering of belvederes, tea houses and statues nestled in the greenery, but from there it veers off in unexpected directions.

There is a synagogue, and Europe’s only artificial volcano, made from boulders that “erupted” with fireworks and lava-like special effects during festivals, with a neoclassical pavilion built into the side containing Franz’s collection of volcano-related items in rooms decorated in Pompeiian style. Beneath the volcano is a stunning labyrinth of passages, arcades, chapels with skylights, and alcoves including one with an openly homoerotic Greek sculpture.

In the park, a dozen or two bridges each in a different style document the history of bridge design from the Stone Age to the Enlightenment.

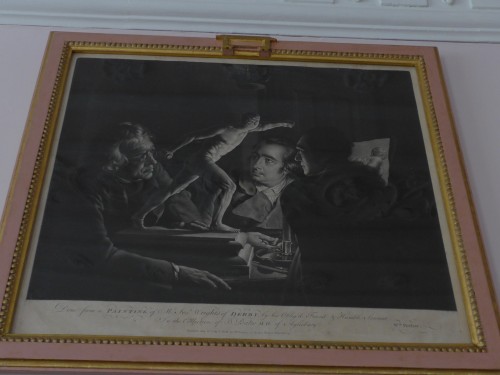

Much of Prince Franz’s inspiration to rediscover the worlds of classical Greece and Rome came from his association with Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), often called the father of both modern archaeology and art history, and a more or less open homosexual in his day.

If the name Dessau sounds familiar, it’s because the Bauhaus art and design school – including the iconic Walter Gropius buildings – was located there after moving from its earlier home in the town of Weimar. The Bauhaus also has UNESCO World Heritage status, but even devoted architecture fans may find themselves wondering if the buildings push the minimalist purity so far it crosses the threshold into almost-blah. I’m as big as Bauhaus fan as any, and I have been in many ultra-minimalist buildings by many famous architects, Bauhaus and otherwise. The best were sublime yet human, elemental yet thrilling. Surprisingly, very few actual Bauhaus structures count among these. They’re just too functional; I’m not seeing much connection to human beings or the surroundings. To see what I mean, look at Le Corbusier, whose buildings appear similar at first glance but in fact very much have these connections.

It says a lot that the public programming theme of the Garden Realm for 2017 was ‘tolerance’, which connects the Enlightenment’s eagerness to explore new, unfamiliar and foreign ideas, with Germany’s current and fiercely contested immigration situation and debates about nationalism and openness to outsiders. Counterintuitively, once you look past the first impressions of aristrocratic luxury and powdered wigs, the architecture of Prinz Franz’s open-minded curiosity about the wider world in 1770 turns out to be no less relevant today than the stoic functionalism of early Bauhaus circa 1920.