Despite its plentiful lakes, rivers and canals and its reputation for rainy weather, Berlin is in many ways as dry as Spain or Texas. Yet it uses more water than is refilled to its supplies every year, and hundreds of millions in fines are looming due to ongoing violations of E.U. water protection laws. Solutions will be tough: Berlin has 13 mayors and a bizarre water supply system, the only one of its kind in the world.

Berlin is always seen as a watery place: everyone loves the abundant waterways and lakes and hates the grey damp winter; panic – most of it without basis in fact – over basements being flooded by a high water table is something of a municipal religion. They say it has more bridges than Venice (hardly an accomplishment given that the whole city of Venice could fit inside Berlin’s airport alone and Berlin has 14 times as many people ). The surprising truth, though, is that Berlin is a very dry place with dried-up forests, shortages of water, and extremely low rainfall, in fact less rain than pretty much all of the United States including Texas and Florida apart from the deserts, and less than many parts of Spain and Italy. Berlin probably a has negative water balance, which means more water is leaving the city than is coming in – in other words, the supply is dwindling and will someday run out if drastic action is not taken, although we can’t be sure because the authorities themselves have neither the data needed to find out nor the staff or funding to collect it. The climate crisis is not the main cause of any of this and the problems existed before climate change became severe, although this fact is known mainly among scientists and almost completely ignored by the media and the administration.

Very few people realize that it’s possible for a region to have so little rainfall that it’s almost arid, while also having a cool, mild climate, but that is Berlin’s situation. The city is reasonably well-supplied with trees and parks. But a closer look at the river Spree reveals that if its current was any slower, it would be questionable whether it meets the definition of “river”. It’s not unheard of for the current to stop altogether or even flow backwards. Some of this is natural and some is due to human activity. Low rainfall is normal for the region. Human activities, on the other hand, are the primary cause of the slow-to-backwards river currents and the main reason the forests are drying out, which, again, pre-dates the climate change impacts. These are all consequences of Berlin’s water resource management, historical events, and coal mining in the region. All the factors, natural and man-made, are exacerbated by the climate crisis.

This is more than just trivia for weather fans. It means Berlin needs to manage its water supply just as meticulously as hot sunny arid places do, and stop spending down its water capital. But Berlin hasn’t done that. Thirty-plus years after the Wall came down, the city still doesn’t have a water management plan. Several water supply plants don’t even have formal agreements with the city – in other words they’re literally operating without a permit. Somewhere along the way it was decided, apparently, that devil-may-care and live-fast-die-young are suitable operating principles for a municipal utility.

Before getting into that, though, a look at a few basic eyebrow-raising numbers is in order.

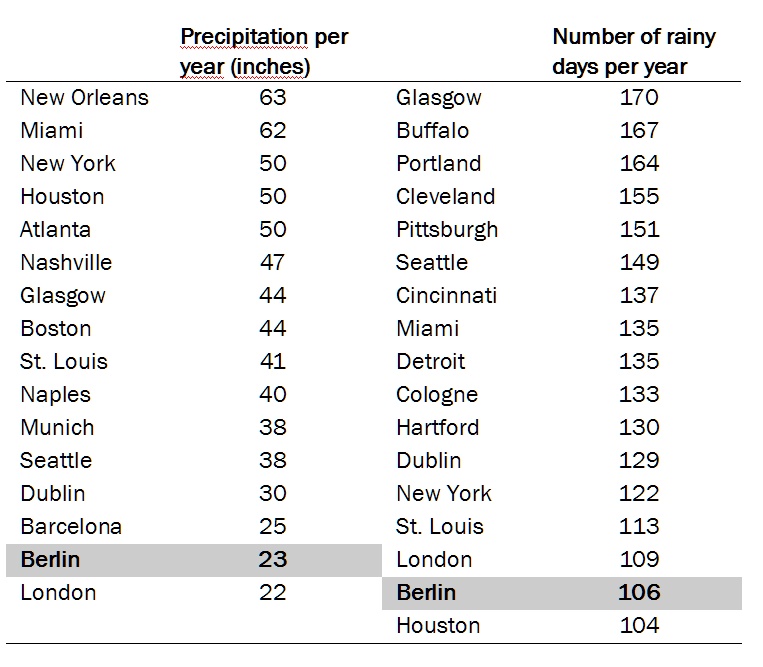

Berlin gets very little rain: As measured by total annual precipitation, Barcelona gets more than Berlin, Naples almost twice as much, New York City and Houston more than twice as much and Miami almost three times as much. For that matter, famously “wet” London is drier than nearly every major U.S. city except Los Angeles.

…and very few rainy days: Houston has about as many rainy days per years as Berlin, New York fifteen percent more, and Miami one-third more.

Berlin has a higher risk of drought than all of North America and most of Africa. The city’s drought risk is defined as medium-high. “Drought risk” doesn’t just mean lack of rain, it also means how much a place depends on rain for its water, as opposed to getting it from large underground aquifers that will last for centuries, and how vulnerable its society and infrastructure are to water shortages – for example, how long its reserves of drinking water would last in a drought. Berlin has a risky combination of very high dependency on very low rainfall; a dense population with a high demand for water; and a water supply infrastructure whose unique design makes it quite likely the most vulnerable of any major European or American city, to disruptions such as climate change.

Berlin has a high risk of water shortages: Its water stress – and that of about half of Germany – is rated as “high” by experts, which designates places that use 40 to 80 percent of their available water every year. In other words, Berlin and half of Germany would come dangerously close to running out of water if a run of dry years were to occur or if the city were to grow rapidly, which Berlin already is, as one of the fastest-growing cities of Europe and for that matter the U.S. Normally, water supplies are renewed naturally by precipitation and river flow, but the annual replenishment of Berlin’s groundwater by rainfall is expected be 40% less in 2040 than it was in 2000. Very few places in Africa or the U.S. have water stress as high as Germany’s, outside of the sparsely populated Great Plains and deserts in the southwestern U.S.

While basements are flooding, forest soils are drying out

The consequences of acting like there’s a lot of water available when there isn’t are already visible. Soils in the state forests on the outskirts of the city are drying out, resulting in the degradation of endangered wetland and bog habitats that have legal protections (like endangered species do) under European Union law. This has triggered legal action by the EU which will result in steep fines if the city does not reverse the trend.

The desiccation is caused by, of all things, a lowered water table – exactly the opposite problem to the flooded basements – which in turn is caused by the city drawing water from aquifers situated underneath the forests instead of from other possible sources. The reason Berlin uses these particular aquifers is that it obtains all its drinking water from within the city limits. It is the only large city in the world to do so.

A water-supply system unique in the world – for good reason

Other cities obtain their water from whatever source – underground aquifer, river, lake – is most abundant and practical, regardless of whether it is located in the city proper. There is absolutely no benefit for a city to get 100% of its drinking water from within the official city limits and nowhere else. In principle it’s not much different from a city trying to subsist only on food grown within the city limits, or only use wood from its own trees, or stone from its own quarries. This is an entirely separate issue from “local food” because “local food” means “grown within 150 miles or so”. No one anywhere has ever proposed defining “local food” as “within the city limits”. (As for urban gardening, regardless of its valid educational benefits it’s physically impossible for it to make any significant contribution to food supplies: researchers have calculated that if the entire surface area of New York City – every square foot – were converted to farms it could only produce enough food to feed 1% of its population, which of course would have to be living elsewhere because there would be no buildings). But the city limits are precisely the boundary that delimits Berlin’s water sources.

For the quantities that a city needs, it makes more sense to get water from sources in the region that lie outside its borders but are more abundant and, ideally, cause less harm to the environment, than from sources that are on-site but scarcer, more harmful to the environment and/or more expensive to manage. But that is precisely what Berlin has chosen to do.

Centuries of decentralization have left their mark

The situation is a bizarre, costly and environmentally harmful relic of Berlin’s unusual 800-year history that has resulted in a piecemeal, disunified water system that no one has bothered to do anything about. To trace its origins you have to start with the fact that until the shockingly late date of 1871, Germany had never even been a nation and Berlin was never a national capital, with all that implies, like France and Paris had been for centuries, England with London, or Italy with Rome. Berlin had only been the capital of one particular medium-sized kingdom (Prussia) among dozens, at times hundreds, of little dukedoms and principalities that only formed loose, shifting, decentralized associations like the Holy Roman Empire and never a nation per se.

Even after Germany became a nation in 1871, the place we call Berlin wasn’t one city but eight separate cities and towns and 86 communities, all administratively independent. Finally in 1920 they were consolidated into 20 districts, later 23, then consolidated again into 12 in 2001.

A city with 24 mayors

But these districts have nothing in common with the districts, boroughs, or wards in other cities. Each has a complete and autonomous city government with its own mayor, council, assembly of members drawn from subdistricts within each district, a full suite of administrative departments and its own autonomous self-contained budget. But this all exists at the citywide level too, resulting in tredecuplicate (like duplicate, but for 13) administrations – 12 fully separate and autonomous district planning departments plus one citywide planning department, 12 autonomous parks departments plus one citywide parks department, 13 health departments, 13 housing departments, 13 education departments, 13 streets departments, 13 of everything, in a city smaller than Minneapolis/St. Paul. I suppose there were a staggering 24 of everything until the consolidation of districts in 2001.

Although “autonomous” isn’t entirely accurate. In fact they exist in a quantum Schrödinger’s cat state where the district bodies are subordinate and not subordinate to the citywide administration at the same time and no one really knows who has the final say.

All this decentralization left little incentive to build a citywide water supply system. (In the late 19th century, a comprehensively planned sewage system was built, which is beyond our scope here.) Then World War II intervened, and afterwards when East and West Berlin were part of separate countries, comprehensive citywide water planning was out of the question. This set the city on its course of not getting any water from the surrounding rural state of Brandenburg where there is more supply and less demand.

After reunification in 1990, Berlin cobbled together a municipal water system from what was there before, without citywide integration to say nothing of regional integration. Many parts of the city have to autonomously obtain their own water; water can’t be moved between them to suit demand and supply. The boundaries of the water-supply service areas are determined by topography and infrastructure and not by the administrative boundaries of the twelve districts. The result is that some portions of the city that contain forest lands, including critical wet bog forests, can only get their water from aquifers lying beneath the forests, which lowers the water table and dries out the soil. And that’s how you get from the 500-odd sovereign principalities of the Holy Roman Empire to the EU threatening Berlin with fines for habitat destruction. Around 2008 the city, with the help of paid external experts, assessed the problems and came up with solutions. The reports and plans were filed away and, as any municipal employee will admit, utterly ignored. Ten years later, in 2019, it was all outdated and the authorities started the whole planning process again, from zero. Meanwhile the issue of the water company not having contracts with the city sits quietly on the back burner, where it has been for thirty years.

Unintended consequences: when reducing coal mining increases pollution

It somehow fits with Berlin’s surreal history that the closing of coal mines results in an increase in its river pollution. The Rube Goldberg chain of events works as follows.

On the river Spree upstream of Berlin is a major coal mining region. Several coal mines there have been closed. After closure, the mines are flooded, that is, water fills the space where the coal used to be (the coal, of course, is now floating in the air in the form of carbon dioxide, having been burned.) The water for this comes from the river. The volume is so great that it dramatically lowers the water level of the river and will do so for decades until the mines are filled. So now the Spree has significantly less water than it used to, but the same amount of pollution is entering into it, such as sulfur compounds from the mines that are still open, and nitrogen from agricultural runoff. Thus the amount of pollution has been constant while the amount of water in the river has been decreasing, which means the pollutant concentration has been increasing.

The water pollution levels have caused severe damage to the aquatic ecosystems and exceed the legal limits determined by the European Union. As is the case for the degradation of the wetlands, the EU has initiated so-called infringement proceedings against Berlin, which will lead to stiff fines if Berlin does not improve its water quality.

It goes without saying that, despite the reduced river flows, closing the coal mines is a net benefit for the environment due to avoided carbon emissions and the direct impacts of the mining itself. Climate change or no climate change, the mines would get shut down sooner or later anyway, either because they ran out of coal or ceased to be price-competitive with wind and solar.

Background on Drought Risk and Water Stress

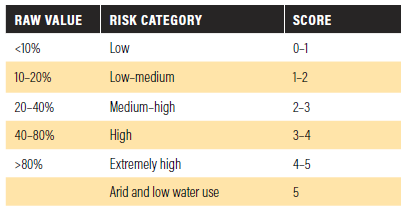

Maps are from the World Resources Institute’s Water Risk Atlas 2019.

Definitions of terms

Adapted from Water Risk Atlas background information

Baseline water stress measures the ratio of total water withdrawals to available renewable supplies, both surface and groundwater. Withdrawals means domestic, industrial, irrigation, and livestock uses, both nonconsumptive and consumptive. Nonconsumptive use means water that is withdrawn and then returned to the source, such as when a factory uses water from a river for cooling or cleaning and then returns it to the river. Consumptive use means water that is not directly returned, such as for agriculture where the water ends up in the crop itself or evaporated into the atmosphere. Available renewable water supplies include the impact of upstream consumptive water users and large dams on downstream water availability.

Higher values of baseline water stress indicate more competition among users. The ratio of water used to water available as a percentage is converted to the following risk categories:

Drought risk measures where droughts are likely to occur, the population and assets exposed, and the vulnerability of the population and assets to adverse effects. Higher values indicate higher risk of drought.

It is calculated using a formula that incorporates the hazard itself (lack of rain based on historical data), the exposure (how many people and how much farmland are in the area in question), and the vulnerability (how sensitive to drought are various social, economic and infrastructure factors – places with high population have high exposure, but they will have low vulnerability if they have ample backup supplies stored in reservoirs).