A sprawling and little-known masterpiece of 1920s-modernist architecture deep in Germany’s rust belt narrowly escaped demolition – and still looks like it came from the future. A must-see for Bauhaus fans.

My birthday present this year was a surprise trip to a disused coal mine. Which was perfect because I’d been dying to go and that’s because this particular mine is not only located in a former rust belt with a fascinating history of environmental destruction and recovery, it’s also the world’s largest assemblage of architecture in the 1920s- and 30s-modernist style (often inaccurately called Bauhaus) outside of – oddly enough – Tel-Aviv.

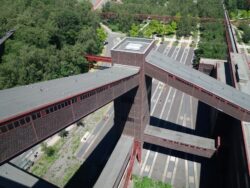

The architecture of both the mine and Tel-Aviv have been designated World Heritage Sites by UNESCO, joining the ranks of Venice and the Grand Canyon. The mine, called the Zollverein, is further distinguished by the natural forest that’s been left to grow unchecked on the open spaces and former spoil tips, resulting in a wooded park with industrial chutes and gangways crisscrossing high in the treetops

There’s a whole fascinating story of the environmental and economic rehabilitation that’s been going on for 30 years, but this has been extensively covered elsewhere. So today will be a break from my usual focus on the environment in order to focus on the buildings themselves, on which there’s close to no information available in English at all.

The mine is something of symbol of how Germany turned around one if its declining rust belts, near Cologne on the opposite side of the country from Berlin, where the jobs in mining shrunk from about 500,000 in 1960 to 250,000 just ten years later, and then to 15,000 by 2010. To put that in perspective, the total number of coal mining jobs left in Germany is one tenth as many as were lost in that ten-year period. Yet the country is still behaving as though a timely replacement of coal with solar and wind power, and adequately providing for the displaced workers, is out of the question. The claim is that this would cripple the economy and plunge the country into ruin, which of course is nonsense..

The site, which is the size of Manhattan’s Financial District, was rescued from demolition and painstakingly restored in the nineties and aughts. The preservation was carried out in a noncommercial and nonflashy way that stringently preserved the visual integrity. None of it, astonishingly, was sold off for luxury condos, offices for tech elites, or hotel/retail developments, as would be likely happen if this were Berlin (that would be a very Berlin thing to do) or the U.S..

The mine first opened in the 19th century; in the late 1920s it was completely rebuilt in the modernist style which was radically avant-garde at the time. It must have looked shatteringly futuristic back then because it still does today.

In fact, though, the architecture is far more graceful and appealing than would be expected from a modernist coal mine. Although the exteriors are almost entirely constructed from a single type of brown-red brick framed in steel painted a lighter brick red, the bricks have earthy, natural color variations that impart a depth and an organic feel and soften the minimalism. The windows are nearly all variations on a single shape. But from these simple elements an astonishingly rich variety was achieved. It’s elegant and austerely beautiful and I can’t believe it’s not featured in every history of modern architecture. I’ve been to several world-famous housing developments from the Bauhaus era. They’re interesting, very spartan, functional. But definitely not spetactular like the Zollverein.

The massing of the buildings and placement of the windows form countless fresh and inspired configurations that respond to each building’s function. At every turn I was struck by the way simple boxes could come across as harmonious and inspired as they do here, rather than soulless and punishing as they usually are – for example in some punishingly, even sadistically hideous buildings from the 2000s just across the street. I call it the You Really Have To Hate Humanity A Lot To Create So Much Ugliness style of architecture.

Needless to say, when the mine was in operation, serenity and harmony would have been utterly absent from the site and the lives of the workers. The pollution and noise were devastating, the working conditions brutal, and the health impacts severe. Apart from the respiratory ailments, on the tour they said workers were sometimes glad to lose their hearing because the noise was so unbearable – only to find the vibrations were every bit as punishing. As appealing as the architecture is, I can’t imagine it alleviating the suffering of the workers to any substantial degree.

Nowadays there’s swimming, ice skating, concerts, convention halls, a few artist’s workshops, office space, and only a bare minimum of restaurants and shops. Don’t get too excited – you can’t go up on the structures or climb around on anything except for one or two gangways and a rooftop.

The rescue of Germany’s rust belt

The surrounding region, known as the Ruhr Valley, was once the largest and most polluted industrial and coal mining area in Europe. Imagine if the industrial stretches of northern New Jersey from New York to Philadelphia and the Lehigh Valley, an area about the size of the Ruhr, were unrelieved by beautiful, charming leafy towns, the Princetons and New Hopes and Morristowns and by the extensive natural woodlands and wild-growing forests of the Highlands. There’s nothing approaching these kind of wild refuges anywhere near the Ruhr or for that matter almost anywhere else in Germany, where “forest” normally means monocultures or heavily-managed woodlands whose biodiversity approaches the lowest levels that are physically possible and which don’t undergo natural successional growth.

Then starting in the 70s and 80s, most of the mines and industry shut down due to globalization. (Here you have to ask if the people flying into rage over the conversion from coal power to wind and solar also had the same outrage over the shipping of millions of industrial jobs to China.) Since that time, the area has undergone a massive transformation, the economy revived, and the toxic sites remediated. Today it’s a tidy and economically stable area with light industry, pharmaceuticals and the like.

Does it have inspired, beautiful urban planning and thriving small-town Main Streets? Or responsible environmental stewardship? Is it admired by the enlightened urban planning community or featured in urban design magazines? No, no and no. It’s sterile and ugly, the town centers are dying just like in the U.S. and there’s virtually no nature anywhere, in any accepted sense of the term (forest that hasn’t been disturbed in 100 years or so, or streams allowed to run their natural course). It’s still the car-oriented sprawl that has been championed since the 60s and public transportation is a shambles by the once-high German standards.

And yet by American standards – low as that bar may be – the public transportation is excellent. If there isn’t actual nature, countless spoil tips and landfills are being allowed to reforest. They should be semi-natural in another 50 years or so, provided the forest authorities refrain from the aforementioned highly unnatural and regimented forest management practices. The region is crisscrossed by long-distance bike paths and well-documented industrial heritage culture routes.

There’s virtually no poverty comparable to that in the American rust belt, no opioid epidemics, and everyone has health care. One of the continent’s dirtiest rivers, the Emscher, has undergone one of the world’s most comprehensive clean-up efforts. Stormwater and flood management in the Emscher watershed have been planned using technologies variously known as green infrastructure, nature-based solutions, and low-impact development, a type of engineering where Germany otherwise lags a good two decades behind the state of the art. Generous public funding supports the arts to a degree unknown in the U.S.

The insides aren’t all that accessible

Sadly, you can’t see much of the tremendous, awe-inspiring innards of the buildings. You can to take a brisk-paced tour that goes through a building or two, and you can visit the nicely-executed Ruhr Museum which is nestled amongst the machinery and intact structures of the large coal washery building, and that’s pretty much it. Not as much as you’d expect given the size of the complex.

Ruhr History Museum

Restaurants

Not really Bauhaus

A lot of architecture fans would call the architectural style here Bauhaus. That’s not really the case and it doesn’t fit with what was actually going on in architecture at the time. The Bauhaus didn’t even start teaching architecture until 1927, by which time the Zollverein had already been designed by architects who weren’t connected with it and hundreds of prominent and influential buildings by architects such as Bruno Taut had already been built in Germany and elsewhere that nowadays are called “Bauhaus” more often than not.

The Bauhaus was a design school that originally was devoted to other areas such as graphic and industrial design. It was an important element in the development of modernism, but this had been going on since the 1890s and it didn’t originate in the Bauhaus. In fact very few buildings ever actually came out of the Bauhaus. There were really only ever two widely recognized architects associated with it, the founder Walter Gropius, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

I think people tend to say Bauhaus just because it’s a convenient catchy word and is well-known in so many other areas such as furniture and graphic design, and because the more accurate, broader name for 1920s-30s modernism – the International Style – sounds clunky and vague.

The UNESCO site in Tel-Aviv, officially known as “White City of Tel-Aviv – the Modern Movement” consists of 4,000 buildings built starting in the 1930s by many architects, mostly from Russia and Poland, a few from Germany, who immigrated to the precusor of what is now Israel, which was then known as Mandatory Palestine. A few had studied at the Bauhaus; many more were influenced by it. Naturally it’s a much larger and more complete realization of what the International Style and the Bauhaus were all about than the Zollverein. It’s important enough in the worlds of both architecture and geopolitics that when Germany issued a postage stamp to commemorate 50 years of Germany-Israel relations, it featured the White City.