A digression from environmental topics. Believe it or not we saw all this in five days not counting the travel day on each end. One of my favorite things of all time anywhere was the house or rather castle of the greatest tapestry weaver of the 20th century which you can go directly to here .

Table of Contents

Atlantic seashore:

Arcachon – zany Victorian resort villas

Oyster farm villages

Cap-Ferret

Dune of Pilat – tallest sand dune in Europe

Dordogne and nearby:

St-Emilion

Beynac Castle – dungeon, battlements, ramparts, boiling oil, the whole megillah

Domme and Sarlat

Marqueyssac Gardens – famous ‘pile of blocks’ topiary

Padirac Chasm – 300 foot deep hole in the ground and cave

Rocamadour – medieval churches built into cliff side

Castelnaud castle – like Beynac but different

Lascaux – the famous stone-age cave paintings

Jean Lurçat, my favorite artist

Bordeaux

The first row is the Miroir d’Eau (water mirror), a plaza with water less than a quarter-inch deep that turns into a cloud every fifteen minutes. On that day the wind prevented much of a cloud from forming so I found better pictures online (second row). Miroir d’eau is originally a term for the reflecting pools in front of Baroque palaces. Click here for video.

Bordeaux has whole neighborhoods filled with these little late 19th-early 20th century row houses called échoppes. I wouldn’t exactly call them beautiful or charming but they are interesting. Also these neighborhoods have hardly any trees due to the hot dry climate, Bordeaux being closer to Spain than to Paris. The streets are narrow and the sidewalks are only wide enough for one person. Normally échoppe means a small shop, stall, or chisel.

Arcachon

Arcachon, on the Atlantic seashore, was built as a health resort in the 19th century and has many flamboyant villas from that time in styles ranging from medieval castle to Swiss chalet to the style known in the U.S. as gingerbread.

Oyster farm villages

Arcachon Bay is filled with little oyster-farming villages such as Le Canon and Port de Larros.

Cap-Ferret, the Hamptons of France

An unassuming beach village between Arcachon Bay and the Atlantic shore which has become something of the Hamptons of France. Unimpressive 1970s bungalows sell for millions. Not to be confused with Cap Ferrat on the French Rivieria, playground for Russian oligarchs, African kleptocrats, the very top celebrities and other world’s biggest tax evaders, which has the second most expensive real estate in the world after Monaco and before London and Hong Kong. We had lunch and went to the beach.

Dune of Pilat, Europe’s highest

Click here for video.

St. Emilion

The main town in the Bordeaux wine country, with medieval buildings built directly into the rock, such as the “monolith church” and various chapels and catacombs.

Beynac Castle

Now we’re in the Dordogne region. Dordogne is pretty much just another name for Perigord which is more or less the main region in France for a variety of things: medieval castles, caves with Stone Age paintings, regular caves without paintings, truffles, duck and geese including foie gras, and walnuts. Hard to believe, but cars and small trucks can fit in the tiny twisting cobblestone lanes and there are little garages tucked into the medieval foundations at improbable angles.

Domme and Sarlat

Two more towns in the Dordogne.

I thought this market in an old church that had been decommissioned since 1794 and since then was used for things like storing timber and coal was extraordinary and unique but then a friend informed me there’s one like it in the small town in Kentucky where she lives. Still, the huge black metal doors are very dramatic and have a quotation from the great post-modern philosopher Jean Baudrillard: “Architecture is combination of nostalgia and extreme anticipation”.

The stone building is a “lantern of the dead” from the twelfth century, of which there are about 100 in France, and no one knows what their purpose was and there are no explanations in written records from the time. They’re not located near cemeteries. One source I read made it sound like they have no door or stairs or other way to get into the room at the top with the windows but this one does.

Marqueyssac Gardens

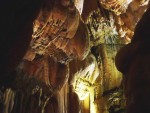

Padirac Chasm

Click here for video.

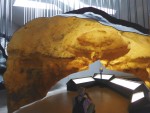

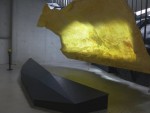

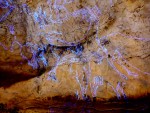

This is a 300 foot deep vertical cave, basically a giant natural hole in the ground. At the bottom it leads to a chain of caves with an underground stream, a “Lake of Rain” with a perpetual gentle rain shower, a 300 foot high dome and other formations.

Everything in the cave is so strange and devoid of reference points to the surface world that even the photographs on the official website are hard to make sense of. There’s no sense of scale so you can’t tell how big things are or get any spatial orientation. They used to have a spectacular online archives of historic photos, postcards, brochures, diagrams and more going back over 100 years but they got rid of it all around 2020. Some of it has been rescued by the Internet Archive, for example here and here but the pages may not actually work.

Rocamadour

Rocamadour is a complex of churches built on the side of a bluff as a pilgrimage site. It’s so steep and narrow you can’t really capture what it looks like in photos unless you were to take pictures from across the valley.

Castelnaud Castle

The region’s UNESCO Biosphere Reserve status is at risk

Click here for video.

These are just two of the Stop the Valley Massacre banners we saw on the way to Castelnaud Castle, which are protesting the construction of bridges and highways to allow as many of the largest tour buses as possible to drive directly up to a couple of villages such as Beynac-et-Cazenac, population 500. Right now the landscape looks largely as it has for centuries. From many vantage points, the new bridges and wide roads would be just about the only obviously modern structures visible, and the Dordogne Valley likely would lose its designation as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. Construction began in 2018 despite vehement opposition apart from a corrupt village mayor with an uncle in the higher ranks of the planning authorities and a handful of hotel owners. On December 28 2018, France’s highest court issued an injunction that halted construction; stated its finding that the arguments for permanently halting construction were sound; and referred the case to a regional court. In these situations in France, lower courts are not obligated to concur with the high court but normally they do. An online petition opposing the project is here.

My educated guess is that many of the same Yellow Vest protestors smashing windows out of rage at Macron for cost-cutting support the village mayor who somehow got $40 million (baseline starting cost, final cost open-ended) for the debacle.

Turns out there’s almost no way to take a decent picture of a castle. Outside, you can’t stand back far enough because they are perched on steep rocks, which is the whole point of a castle, to prevent invasions by having as little level ground as possible (hence the two aerial photos from online) and inside the rooms are either too big or too small to capture. At any rate they are mostly empty because obviously the thrones and banquet tables and mead tankards were gone centuries ago. Castelnaud was built on and off from the 13th to 17th centuries.

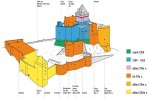

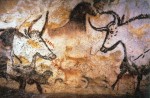

Stone-age cave paintings at Lascaux

Lascaux is the world’s most well-known and I believe largest stone age cave-paintings site. It was discovered in 1940 when a dog chased a rabbit into a little hole in a forest. The dog’s owner got curious when he tossed rocks in to drive the rabbit out and could tell by the sound there was a large space.

In 1963 the cave was permanently closed to the general public because humidity and carbon dioxide from their breath was causing irreversible damage to the paintings. A full-size but incomplete replica opened nearby in 1983 and a second, complete replica opened in 2017. However mold damage has continued due to allowing too many professional visitors and an inadequate climate control system.

The really great supermodern visitors center (video here) has an airplane-hangar-sized hall with replicas of a dozen portions of the walls along with highly advanced computer interactive displays to show things invisible to the naked eye. Trust me, I always hate it when museums have computer screens and this is a brilliant exception that proves the rule. For example at one station when you point the little hand-held computer/video camera they give you at the ground, stone and clay artifacts appear in the places where they were found, and you can pick them up on the screen and turn them around in three dimensions.

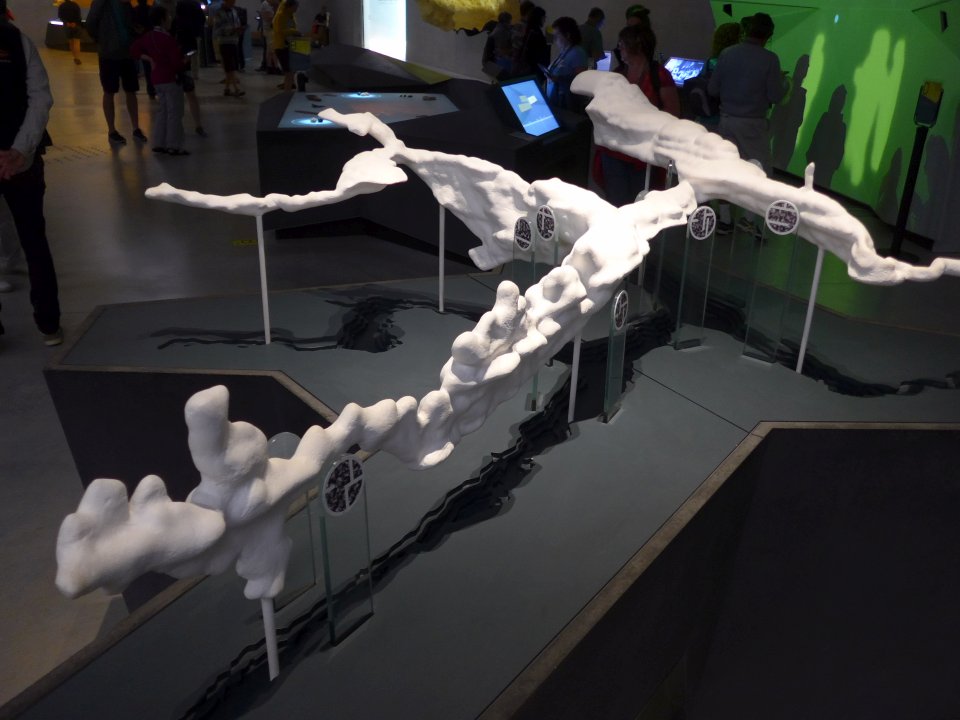

This is a model of the whole cave, as if you made a cast of it by filling it with plaster. When you point your handheld screen at it, a 3d image of the inside walls pops up. You can move and turn the handheld in every direction all around the model and walk around it and the image follows your “location” within the cave. Both of these are in the video.

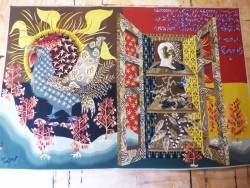

The tapestries of Jean Lurçat

Saved the best for last. We made a pilgrimage to a remote village deep in the Occitanie region in southwest France, where Jean Lurçat (1892-1966), one of my top favorite artists, lived in an austere hilltop castle (video is here). His medium was tapestry, which has now largely been abandoned, forgotten, and superseded by the looser category of fiber arts.

Tapestry (definition of tapestry here) was never very common because it is the most cumbersome, impractical and labor-intensive art form: it almost always involved enormous sizes – eight by ten feet is the low end, 20 by 30 is not uncommon – requiring looms so large that artists seldom if ever wove their own.

The tapestries were made in central workshops by trained weavers, with anywhere from one to a dozen working full-time for a year or more to complete one tapestry. The main workshops were Aubusson, Gobelins and Savonnerie. Compounding the impracticality is the fact that there’s no way to see the tapestry until it’s finished. The whole thing is wound onto a giant spool inch by inch, yard by yard, month after month as work progresses. Only when it’s complete can it be unwound and viewed. Even the yard or so that’s being currently woven can’t easily be seen, because they’re woven from the back side.

Thus tapestries have rarely been owned by individuals apart from the aristocracy and even then only the higher ranks. Originally they were used in castles, palaces and churches as combined insulation and decoration. After the invention of central heating they spread to elite high-level government offices, embassies, theater and hotel lobbies and cruise ships. Sometimes they hung in schools, hospitals and non-elite government offices, I think more in Communist countries but I’m not sure. Small home looms owned by individuals have always existed but that seems to be have been a minor branch of the tapestry world and primarily a domestic craft made and displayed in people’s houses rather than in public, until so-called fiber arts became popular in the 1960s.

Close-up views showing the weaving

Other things Lurçat designed besides tapestries

Lurçat’s castle, Château de Saint-Laurent-les-Tours

Inside

Another reason you don’t hear much about tapestries is that 95% of them, pretty much all the tapestries made from 1550 to 1940, are boring.

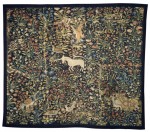

Good vs. boring tapestries

Up to around 1550, the medieval and early Renaissance style, as in the famous Unicorn Tapestries, had a simplicity that is still appealing and fresh today. Then for the next 400 years, no one attempted anything other than mimicking florid, elaborate Old Master paintings as closely as possible. Somehow they’re extravagant and lifeless at the same time and they all sort of look the same whether depicting a famous naval battle or an allegory of poetry. Even during the exciting cubist period in art in the 1910s-20s, tapestries were pleasant but boring copies of cubist paintings. Then in the 1930s and 40s, Lurçat became the first person in centuries to exploit the possibilities of tapestry for making artistic statements that really use the yarn and tapestry medium to their best advantage. Several others followed in his footsteps during a brief golden age of modern tapestry that lasted from the 40s to the 60s. Since then, the possibilities of using yarn and textiles for art have branched off in countless experimental directions, often more like sculptures. Wall tapestries in the older sense are seldom made any more and tend have clumsy, artistically shallow abstract designs that mainly just serve as ugly modern art for corporate boardrooms.

Wait remind me what is a tapestry again? True tapestries are woven on looms that have plain white strings running in one direction, and perpendicular to those (i.e. going across), weavers weave wool yarns in a simple over-under fashion, which conceals the white string. For the most part this was the only weaving method used for centuries up until the 1960s when free, diverse experimentation took hold. The famous Bayeux Tapestry depicting the Norman Conquest is not a tapestry at all. It is embroidery with a needle and thread on white cloth. The ‘tapestries’ from India that are popular among college students as bedspreads and wall hangings, or at least were from the 1960s to 90s, are also definitely not tapestries. They are just cloth with printed designs and sometimes embroidery like the Bayeux Tapestry but done with machines.