Can we say “we told you so” now? Ignoring ecologists’ warnings about bad land management – along with poor governance and costcutting – caused those deaths at least as much as the climate crisis did.

Last week twice as many people died in floods in one small area in rural Germany than die in the entire U.S. in an average year of floods and hurricanes combined. In the media and the general public the climate crisis is taken to be a primary cause of the disaster and its 242 deaths, 184 of them in Germany. This is factually incorrect.

Although the climate crisis is well on its way to being the biggest environmental catastrophe in human history, in this case it’s being used as a scapegoat to deflect attention away from decades of bad land management, flood planning and disaster preparedness. Germany flagrantly and consistently ignored the most basic principles in these areas, defying the urgent pleas of experts in many disciplines. This left the region vulnerable to a degree most people can’t imagine could even exist in a modern country.

Here’s how we know this. Hurricane Sandy, the largest in North American history, affected the entire eastern U.S. and Canada and the Caribbean over ten days, whereas the European storm affected a region with a tiny fraction of the area and population (maybe 1/1,000th?) over just two days. But Sandy only caused twice as much damage and two and a half times as many deaths.

One possible explanation would be that the European storm was many times stronger and more intense than Sandy – thousands of times stronger by my rough estimate. But that’s not the case. The only other explanation is that Germany was somehow more vulnerable – in other words, a given amount of rain per hour per square mile caused many times more deaths in Germany than in eastern North America, and in a rural area at that, not in a population center. And that’s what happened.

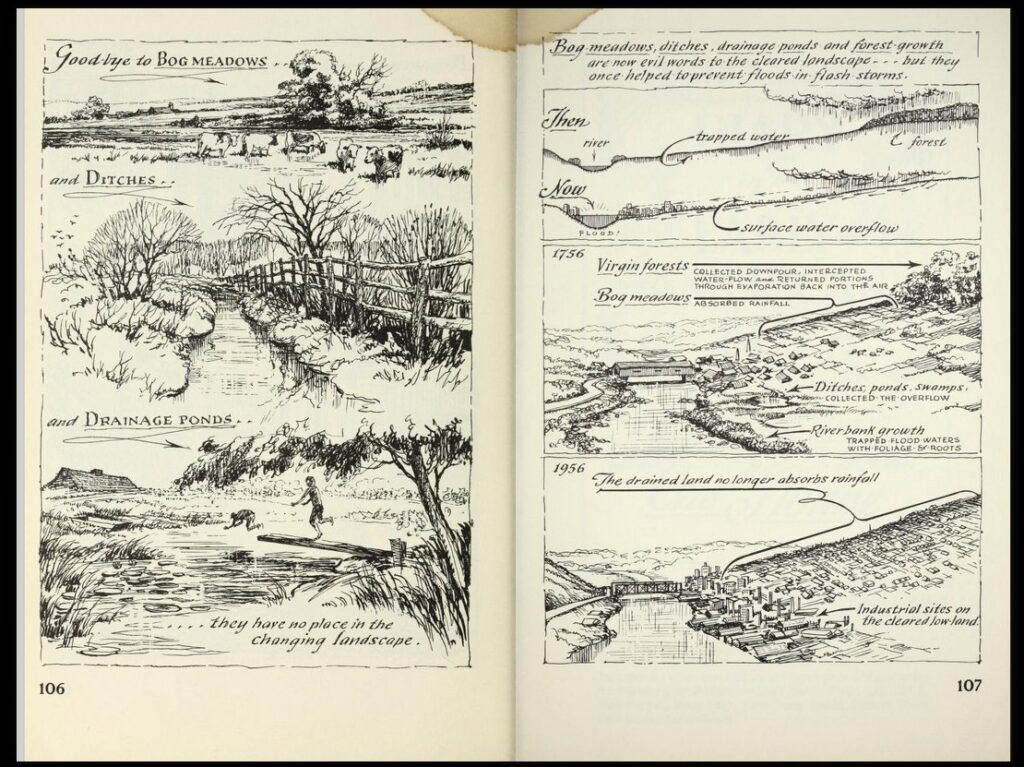

The principles of hydrology and prudent land management that the German authorities ignored are not new or controversial. The fundamentals have been understood for roughly a century and in some cases, such as “don’t build in a flood plain”, millenia. They’re things everyone learns in mid-level college courses in the respective fields. And they predict precisely these kind of disasters. The overarching principle is that effective flood protection requires using the earth’s natural flood defenses instead of trying to use concrete structures as a weapon to beat nature into submission, and when concrete is used, it must support resilience to heavy storms. Doing so would not only protect property and human life but reduce the harm to soil, water, flora and fauna caused by urban development.

The clearest explanation of the situation I know of appeared, interestingly, in a book about landscape history from 1956 (above), and it explains perfectly the conditions that enabled last week’s floods, and nearly all urban floods everywhere.

Flood protection that works with, rather than against, nature is only possible, firstly, if it’s planned and coordinated across landscapes and regions, and secondly, incorporates new understandings and developments in the field.

There’s only one way to achieve the necessary coordination and it’s called government, and there has to be some degree of regional cooperation. What doesn’t work for landscape and flood planning are approaches such as every-man-for-himself individualism, neoliberal politics, “small government”, or the dispersing of collective responsiblities to too many discrete actors. The very purpose of the neoliberal approach of leaving things up to “the market” and reducing the influence of goverment deters precisely the kind of regional coordination that is necessary to prevent these kinds of disasters. Excessive federalism, or decentralization – the devolving of decisionmaking onto inappropriately low levels of government – is a different approach with similar results. This occurs when decisions that should be made at the federal level devolve onto states or municipalities (or states’ powers devolve onto counties or towns). “States’ rights!” is just as much a kneejerk small-government answer to everything in Germany as it is in the U.S.

Secondly, nature-based flood control only recently started to be rediscovered by the engineering and government worlds and requires openness to new – or rather new-old – thinking. But many practitioners in these circles are sluggish to adopt new ideas and still consider nature-based solutions at best exotic and untested, at worst the destructive fairy tales of rainbow-and-pony hippies who want to return the world to the middle ages. This is especially pronounced in Germany, more so than in any of its peer countries. While many nations are moving rapidly on nature-based solutions, Germany remains uniquely impervious to new or foreign ideas and is lagging ever farther behind the times, not just in terms of nature-based flood control, but in many other environmental fields.

The consequences of all this? Over a hundred people were killed last week by the neoliberalism, the overfederalism, and the resistance to proven ideas from outside.

Disasters can only occur where there’s vulnerability

All impacts from natural disasters arise from two things. One is the intensity of the cause, which in this case was a storm exacerbated by climate change. I won’t discuss this further because there’s plenty of information on it elswhere. Here I want to focus on the second factor, which is vulnerability to harm – how much a thing can resist damage, or tolerate some damage and then recover. Germany’s vulnerability to harm was deepned by poor ecological planning and chipping away at government services in the following ways:

- Too much paving: Paving over too much open land makes the stormwater flow quickly into the rivers instead of soaking into soil. This worsened the floods enough to cause many of the deaths. “Flash floods” don’t just happen because of sudden heavy rain, they happen because of too much pavement. Germany – which is a little smaller than Montana – paves over an area equal to 120 football fields per day. That’s like adding a city the size of Frankfurt every year.

- Annhilation of natural rivers: The rivers in the regions had been straightened so they no longer meander like they naturally do, and the wide natural foodplains that normally absorb great quantities of flood water had been eradicated. Both of these things squeeze the water in the rivers into a small area and make it flow faster and more prone to overlowing the banks. If you wanted to cause as many bad floods as possible this is exactly how you’d do it.

- Neoliberalism, austerity and small government: Forty years of insistence that markets will solve everything, government is the problem, and public spending is the enemy is one of several reasons why Germany has what could be the worst emergency warning system of any advanced, rich country. There was a test of the system last year, and it just plain didn’t work. The austerity has also decimated the environmental protection agencies so they have few personnel left to address the paving and river-straightening (“channelization”) problems.

- Pathological federalism: Germany tends to push as many decisions as possible to the lowest level of government possible. In this case it meant the federal or state government’s only duty was to provide the basic weather information to the towns. So each town or county essentially had to create and manage its own emergency warning and planning systems. That’s a bad way to do things and the way we know this is that it made people die.

- Cultural factors: Then course there are the people who won’t flee a danger zone even when adequately warned. I suspect this caused a lot of the deaths. It’s a cultural-psychological-social issue and honestly I’m not sure you can do much about it. You would think the ones who get rescued after staying put should be sent a bill for it unless they can prove they had clear and indisputable reasons. It’s only fair to the taxpayers.

All these factors are not unique to Germany. They play a role in most flood-related disasters in the richer countries, although the federalism is especially pronounced here. Will Germany learn from the 180 deaths and make any changes? Angela Merkel’s successor as the next chancellor after the elections in September, provided their party wins, was asked this question and his answer was, “You don’t go changing your policies just because of something that happened on one single day.” He’s the governor of the state that had the floods – in other words, if the disaster were to be laid at one person’s feet, it would be his.