This is the river Isar in the middle of Munich, just blocks from the city center. Today it looks like a wild natural river but until a few years ago much of the greenspace along the shores was orderly and park-like, the banks straightened and stabilized with stone, concrete and earthworks. This is the story of how a city with a stuffy, uptight reputation (whose accuracy I neither verify nor refute) tore out the orderly, linear shores and restored the river to about as wild a state as possible in an urban center, embracing nature in all its wildness and messy, ecologically healthy vitality – something which even places that are said to be the opposite of stuffy (ahem, Berlin?) are often slow to do.

Before

After

Bavaria – conservative, yet super pro-environment

Munich is the capital of the state of Bavaria, which is – as I’ve mentioned elsewhere – sometimes called the Texas of Germany: both are conservative, strongly religious, boastful to the point of nationalism about their identity, and located in the south. Both are their county’s largest state and the only one that was once a sovereign nation (if you want to split hairs, Alaska is larger and humble, mild-mannered Vermont was once a republic, and California was too, for 25 days). The analogy, however, has two major flaws. Bavaria is arguably the most pro-enviroment German state, its only rival being, perhaps, Baden-Württemberg. Certainly Berlin (which is actually a state) is no rival, for it performs at level markedly lower than its questionable reputation as an eco-capital would suggest. Whereas no one has ever accused Texas of environmental leadership. And in fairness it must be said that Bavaria’s environmental record is far from spotless, for example in having produced the last two, flagrantly anti-environment and corruption-scandal-plagued Ministers of Transport in Merkel’s cabinet (not to mention multi-talented – they are both plagued by racism scandals, too.)

Munich is no Portland, to put it mildly

Nor has Bavaria the traits that are associated with the places in America that have high levels of environmental awareness and stewardship, such as Vermont, Oregon or California: free-thinking independent spirits, DIY counterculture, progressive viewpoints on topics such as gender, sexuality, ethnicity, spirituality and recreational drugs, and resistance to capitalist and patriarchal conformity – not by a long shot. It’s hard for Americans to wrap their heads around the idea that cultural conservatism can coexist with serious, committed environmental conservation. Then again, environmental conservation is in fact “conservative” in the positive, but nearly obsolete, sense of wisely prudent.

As for their largest cities, Munich frequently tops most-liveable-cities lists, as rated both by Germans and by outsiders, on account of its beauty, culture, prosperity, safety and all-around high functioning, which not even Texans can claim of Houston. Politically it is not as conservative as the rest of Bavaria. All of which is to say that when you combine trailblazing environmental stewardship and an engaged populace with lots of money and competent institutions, you can do things like return a concrete-lined canal-like urban river to a reasonable facsimile of wild nature in the middle of a city, which Munich has done.

From 2000 to 2011, the city tore up banks of earth, stone, and concrete that had been built over the course of centuries at various points along five miles of the Isar where it runs through the city center, and through herculean effort restored the channel to a relatively natural state of winding meanders, islets, shifting shorelines, and a mosaic of shallow and deep stretches and slow and fast currents. The result is a linear nature park where fairly natural wildlife habitat coexists with ample room for swimming and sunbathing. This is the polar opposite of most urban rivers, where the city has been built up to the banks and the channel straightened and stabilized.

Before After

Restoring rivers in this way is a top priority in conservation, but it almost always takes place in rural and suburban areas because in city centers there simply isn’t any space for it. In nature, rivers – more or less all of them – are irregular and messy. The channel twists and turns through the landscape; it splits and rejoins in a disorderly braid, and it shifts course every few years or decades as new islets and bars form and old ones dissolve, new banks are formed and old ones eroded, and some branches fuse together while others split. Floods, an entirely natural and normal part of healthy ecosystems, are common due to the mild slope of the banks. Clearly there’s no way to restore an urban river to this state, no matter how much money is available, because the banks are fully built-up and the river has become for all intents and purposes a man-made canal.

Munich, however, was lucky in this respect. For various historical reasons, the city’s urban fabric does not extend right up to the Isar’s banks for much of its length. Even though it had been a commercial waterway (mostly in the pre-railroad era), and still has now-disused lateral industrial canals, much if not all of the Isar has always had more the character of a suburban or semi-rural river than an urban one. Its banks are largely bounded by a band of green space. In some places the riverside zone is narrow, rigidly straightened and park-like, which is to say entirely man-made, while other stretches still retain a fairly natural character with broad winding gravel shores and bars. This is an extremely uncommon situation in the center of large cities.

What the Isar project did was to tear up the more artificial shorelines wherever possible and literally reconstruct the channel in a natural form, using boulders, rocks, gravel, earth, and careful use of concrete and metal where necessary. Everything you see here is the result of painstaking planning by ecologists, hydrologists, engineers and landscape architects.

Gravel bars like these are designed to be inundated when the river is high and more exposed when it’s low, which is how it works in the wild.

The topography and placement of boulders were, like everything else, the result of exhaustive hydrological studies and planning, including a one-twentieth scale model built in a huge shed (the model river was about ten feet wide). Where there used to be a series of linear concrete sills that ran across the river for erosion control, looking like low dams, clusters of rocks now create a patchwork of zones with slower currents and faster, rougher currents. This in turn creates a diversity of aquatic habitats that are required by aquatic fauna and flora, which again is how it is in nature.

The dead trees you see below are typical of a healthy, natural river ecosystem. To the flora and fauna, they are not “destruction” or “waste” but rather critically necessary habitat. Many insects, fish and animals require the nooks and crannies, shade, and patches of calmer water in order to live. The eroding, muddy banks are also indicators of a healthy ecosystem, but just to be clear, that’s not always the case. The cut banks, confusingly, can also be a sign of the excessive erosion that occurs when intense urbanization upstream causes unnaturally strong currents, but that’s not what’s happening here.

Looks nice, but is it wild?

So is it fair to say the river is wild now, or at least natural? No, it does not meet the definition of wild or natural, but it’s certainly much more nearly so than before. Even now the Isar is far from having a natural complement of flora and fauna and it probably never will. Although this stretch may be passable by migratory fish, there are impassable obstacles elsewhere on the river. It will never have a natural flooding regime and it will never be fully ecologically connected to a surrounding matrix of forests. But no one is claiming it’s truly natural, only that it’s more natural than it was, which is absolutely true.

Nature is not orderly in outward appearance. People like the idea of untamed wilderness when it’s in a national or state park but they often want city parks to be tidy and picturesque. Or rather, Americans tend to want some of both: in a good-size park they want a bit of wilderness here (or an approximation), some perfect manicured lawns there.

Germans on the other hand aren’t nearly as fond as of wilderness as Americans are. They’re not especially interested in experiencing it, whether “in the wild” or in small semi-natural patches in cities. The stereotype of the German penchant for order has some truth, and it applies not least to green spaces. The rectangle of pristine grass monoculture is somehow even more popular there than in the U.S.. So it’s surprising that such a rough and untamed-looking landscape got built in the middle of a city with a reputation for stuffiness even compared to other German cities.

On the other hand maybe it’s not so surprising given that Germany is where the science of ecology began and where the word ecology itself was coined; and that it was primarily Germans who first embraced the notions of the holistic mind/body benefits of nature, fresh air, hiking and exercise as we know them today, beginning in the nineteenth century (at least among western cultures; non-western cultures are a different story). Indeed, a pro-nature anti-stuffiness is certainly to be seen in the legal protections afforded to nude sunbathing on the restored banks of the Isar right in the city center. For the record this renowned FKK (Freikörperkultur, “free body culture”, the uplifting German term for what we in English euphemistically call naturism or uncomfortably call nudism) is not unique to Munich but an example of Germany’s distinct lack of body shame. The non-shame is closely linked to that same interest in holistic mind/body health and also dates back at least to the 19th century. The regulations protecting the right to FKK in Munich’s parks were strengthened as recently as 2019.

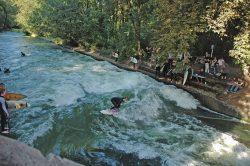

If people have heard anything about the river in Munich, it’s often about how you can surf in it. This is true but there are caveats. The surfing has nothing to do with the restoration or nature, but instead takes place at two or three specific points in canals that were constructed for various practical uses long ago and they only have room for one or two surfers at a time. Other than at these spots surfing isn’t possible because, as in most rivers, the waves are nowhere near large enough. It’s also said you can cross-country ski along the Isar in winter. The fact is Munich has seldom had snow for this, even before the climate crisis. Still, that’s more surfing and cross-country skiing and clothing-optional swimming than in any city center I know of, regardless of whether the reputation for stuffiness is deserved.

Further Reading

Two excellent sources in English are:

– Ecopolis Munich site about Munich’s enviroment including the Isar restoration (archived copy; original site)

– Downloadable brochure from Munich Water Authority (archived copy; original link)

Photo credits: All Wikimedia, under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, except Before/After #1, Google Maps and Before/After #2, Wasserwirtschaftsamt München