Water in cities has a critical role in climate adaptation, from bathrooms to backyards to sewer lines. An engaging exhibit in the Netherlands shows how.

Here’s a detour to the Netherlands, where I saw an excellent exhibit in Haarlem, at an architecture and urban design museum called the ABC Architecture Center, on how the region is confronting the challenges of urban water pollution and the extreme weather caused by the climate crisis.

It was a delight to see an architecture center take on this topic and make it accessible, because it’s not well known in the general public although it certainly is in environmental and urban planning circles in countries such as the US, Netherlands and even China (but sadly not Germany as we will see.) Incidentally, in an unrelated and delightfully quirky twist the ABC was installing an exhibit on one of the greatest Dutch baseball players, who was also an architect and was responsible for the restoration of several important historic buildings such as this one from the early 1600s.

The topic of water in cities in a time of climate change connects everyone’s daily lives – their own yards, utility bills, drinking water, flooded streets – to broader issues of how cities are adapting to the impacts of the climate crisis on water supplies and sources. But this isn’t specifically a climate-based issue, because the problem of polluted stormwater running off of streets and into the storm sewers and streams is severe on its own, even without factoring in the additional burden of climate change..

The exhibit highlights ways to make cities resilient to the increasingly intense storms that climate change is causing, which in many regions alternate with increasingly severe dry periods. This new-ish approach to dealing with stormwater, sewage and water usage – it first gained traction in the 90s – goes by a plethora of names such as green infrastructure, de-paving, nature-based solutions, sponge city, low-impact development (LID), and decentralized stormwater management. Examples include permeable pavement and special sidewalk planting strips that soak up storwmater, and green roofs to slow the flow of stormwater into the sewers.

One such initiative in the exhibit goes by the playful name of Operatie Steenbreek (Operation Stonebreak; steenbreek being the Dutch name for the plant we call saxifrage, which indeed comes from the Latin for stone-break, because it grows in rock crevices). It encourages residents to replace the stone and concrete paving in their patios and gardens with soil and plants, so that rainwater and the pollution it carries will sink into the ground and be filtered by roots and soil instead of running off into sewers and streams. Such programs exist in the U.S. but so far none of the experts I’ve asked have heard of such a thing here in Germany, where a mania for covering gardens and yards with pavement and rocks has been gaining popularity in recent years.

An overview…

A plethora of superb diagrams explains how water circulates in urban and rural landscapes, how it’s used, and how structures should be designed to prevent water pollution, shortage, and flooding. A shown here, these can be retrofitted into the existing city fabric as well as installed in new developments, both of which have been surging in popularity in the U.S. and elsewhere for twenty years. Yet here in Berlin, the consensus among all but a tiny handful of the experts is that such thing is fundamentally impossible in existing building stock – which would be news to the cities around the world that have spent billions doing precisely that.

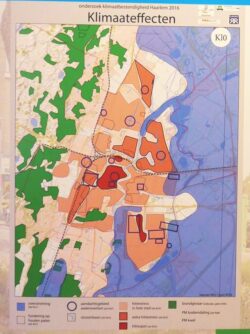

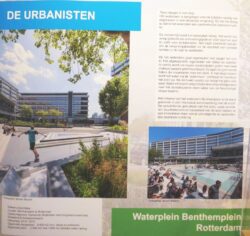

Left: Information-dense maps show the impacts the climate change is having on infrastructure and waterbodies: Right: Showcase project, the Benthem Water Plaza in Rotterdam, a breakthrough in urban environmental planning of global significance, by a firm called De Urbanisten. In dry weather it’s a sunken plaza with bleacher seating and basketball courts. During rainstorms it collects water from the surrounding roofs and pavement, becoming a pond, and releases it slowly into the storm sewers over the next day or so. Just as with raingardens (bioswales) and green roofs, the point is to slow the flow of rainwater into the sewers and rivers and, where possible, let it infiltrate downwards directly into the soil.

Left Family activity with blocks for planning and landscaping climate-friendly streets. Right: Model of how houses are connected to the water and sewer system.

Rain barrels for collecting rain water from roofs so it can be used to water gardens instead of running through storm sewers, which empty directly into rivers. Many cities in the U.S. give these to residents for free and some even pay for the installation, along with other free water-saving devices such as low-flow shower heads, faucet aerators and even entire toilets. I don’t know if they do this in the Netherlands. Berlin doesn’t, and I haven’t heard of it being done anywhere in Germany. Berlin doesn’t even have a water conservation program at all and astonishingly the water authority even discourages conservation on the grounds that the reduced flow would cause the pipes to clog with sediment.