(The German version of this post is here.)

On October 20 came the bombshell-but-utterly-unsurprising news that Total, a French oil and gas company similar to Exxon, Shell and BP, has known about the climate crisis since 1971, and covered it up, just like the others did.

A smaller bombshell is my recent discovery, buried in a book from 1982, that an art museum in a small German town was addressing the climate crisis in that year, in a small but substantial way. The story involves Joseph Beuys, arguably the most important European artist since World War II and, oddly enough, Andy Warhol, the closest there is to an American equivalent of Beuys.

The town was Bielefeld, which has something of a reputation in Germany for being exceptionally bland even by German standards – no mean feat – and is primarily known for being the home of the country’s leading cake-mix company. In 1982 the Bielefeld Art Museum presented Your City Bielefeld: Green, an astonishingly advanced urban greening project which was inspired by and linked to Beuys’ renowned and revolutionary public art project, 7,000 Oaks. Your City Bielefeld comprised an exhibition, book, program of events including walking tours and at least one lecture (“Thoughts on the Ecological Crisis”), and a greening initiative by a citizens group.

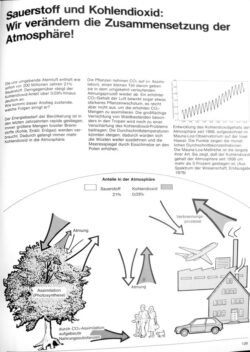

The climate crisis seems to have made only one brief appearance in the book, but all the essential elements as we know them today are present: the increasing levels carbon dioxide in the atmosphere due to the burning of oil and gas in cars, planes, industry, and for buildings; global warming; drought; sea-level rise and the melting of the polar regions. This is basically everything you need to know in a nutshell, and there it was in Bielefeld, a sort of Peoria of Germany, in 1982.

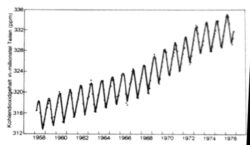

Even the celebrated Keeling Curve is included. This graph of the increasing carbon dioxide levels was first published around 1960 and is known throughout the science world as the first clear and widely-seen depiction of the phenomenon. It was enormously influential – the Rosetta Stone of climate change, so to speak (although the subject has been known to science since the nineteenth century).

Your City Bielefeld is primarily about urban greening from multiple perspectives: trees and their myriad benefits, landscapes, ecosystems, the role of nature in urban planning. This sophisticated approach didn’t begin to catch on widely until at least fifteen years later and it’s still more the exception than norm.

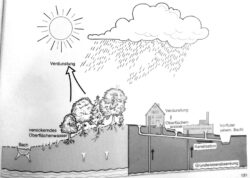

Yet so many other environmental topics were brought up that Your City Bielefeld was practically a condensed crash course in environmental studies, from food webs and geology to urban water resources. It describes the sinking of the water table that occurs when excessive amounts of pavement prevent rainwater from soaking into the soil and recharging (jargon for replenishing) the groundwater that’s been withdrawn for human uses. The situation is nothing short of a crisis and just as with climate change, politicians and the public have only recently started to heed what science and environmentalists have been saying for half a century.

The 7,000 Oaks project is considered one of the high points of socially involved public art. Seven thousand basalt steles were heaped in a boat-shaped pile in a square in the German city of Kassel during the prestigious Documenta art exhibition. Over the ensuing years they were relocated one-by-one throughout the city and next to each one an oak tree was planted, each funded by private citizens and companies.

A municipal tree planting initiative with public participation may not sound revolutionary to us now, when projects like MillionTreesNYC plant a million trees in the time it took Kassel to plant 7,000, and other cities are following suit, but it was a new and radical idea back then. It was also revolutionary to democratize art in this way and invite the public to participate. One of Beuys’ famous mottos was “Everyone is an artist”, by which he meant everyone can and should actively participate in art, and when he said art, he really meant politics and society, because that’s what his art was about. By the time of 7,000 Oaks he’d had an influential, decades-long career of public and performance art that engaged everyday people in actual politics.

Beuys directly inspired Your City Bielefeld and it exemplifies his vision for a melding of art, politics and community participation. The museum’s director was in contact with Beuys and in 1985, when 7,000 Oaks was short of funds, Warhol, Keith Haring and thirty other artists created works to be sold to benefit the project and they were exhibited at the Bielefeld museum.

“I like the politics of Beuys. He should come to the US and be politically active there. That would be great… He should be President.” – Andy Warhol

Beuys and Warhol don’t have much common beyond their stature and even there, Beuys is considered the more nuanced and profound artist. Where Warhol embraced consumerism, celebrity, the superficial and the banal, Beuys’ subjects were politics, nature, history and memory, but he didn’t make art “about” politics; his art often simply was politics and sometimes he simply just did politics. He was a co-founder of the Green Party and a candidate for parliament, surely the only candidate in any country to date whose artworks are in major museums around the world.

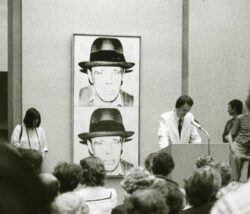

However, history has largely forgotten that Warhol designed a campaign poster for the Greens in 1980. In the same year he added Beuys to his wildly popular series of silkscreen portraits of legends such as Marilyn, Elvis, and Mao. “I like the politics of Beuys. He should come to the US and be politically active there. That would be great… He should be President,” he is reported to have said.

Whether Beuys was aware of the small role that climate change had in Your City Bielefeld remains to be discovered. He was, however, definitely involved with its push for city greening in the form of a proposal for a “green ring” of trees to line the ring road that follows the path of the city’s long since vanished medieval wall. At the opening of the benefit exhibition in Bielefeld, a handful of trees with accompanying basalt steles were planted in front of the museum as an expansion of 7,000 Oaks.

It took seventeen years of campaigning by citizens groups for the Green Ring to be realized. Finally in 1999 the last tree was planted.

Today the ring looks a bit sterile. Maybe that’s just Bielefeld’s distinct lack of charm, or it could be because the trees are set in featureless monoculture grass strips, and they’re small. No one’s going to single out Bielefeld as an inspired example of how to integrate beautiful and biodiverse nature into a city, not by a long shot.

But given the state of urban greening in general in the 1980s, the Green Ring was quite an achievement. Beuys met with rage and hate campaigns when he tried to carry out 7,000 Oaks. Even today, many if not most Germans see each fallen leaf on the ground as an attack on orderliness if not on society itself and a ticking time bomb just waiting to maim anyone who slips on it in wet weather.

It would be interesting to know if anything else came out of this burst of environmental activity in Bielefeld. It certainly is one manifestation of the thriving German environmental movements of the 70s and 80s against acid rain and nuclear power, and for issues such as self-sufficiency, organic agriculture, solar power. The little seed of climate awareness in Your City Bielefeld was of course no match for the organized campaigns of Big Oil and the complicit politicians. But what about in bigger, more progressive cities?

Imagine how much could have been accomplished in the intervening forty years if a proportionate level of engagement existed and had been maintained all along – let’s say, in a city ten times bigger than Bielefeld, an ostensible world capital of eco-consciousness where the Greens have had seats in the legislature for forty years, and social democratic and progressive parties have held the majority for the past thirty years – for example, Berlin.