From 2010 to 2015, over 100 engaging and innovative land-art installations in Indianapolis raised public awareness of river ecology and water infrastructure. But the once-prestigious museum behind them has since pivoted to crass marketing gimmicks – yoga, craft beer – and the “greatest travesty in the art world in 2017”.

There’s a famous story by Borges about a map that’s so detailed, it’s as big as the territory it describes. A few years ago, the artist Mary Miss made something very similar with oversized map pins installed around Indianapolis as a way to build thoughtful and meaningful connections between its residents and their rivers, streams, lakes and wetlands.

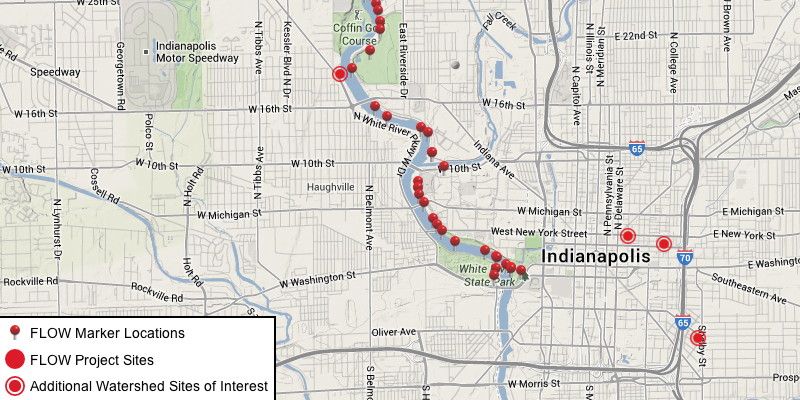

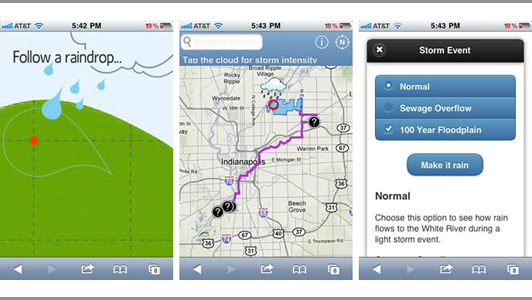

It was actually two projects, FLOW – Can You See The River? (2011) and StreamLines (2015). They consisted of over 100 giant map pins with bright red basketball-size pinheads placed throughout the city to mark various features of the local urban waterways such as small dams and sewer outlets. Further, every site had an ingenious interactive installation that not only provided multimedia information about the water features, but also physically engaged the viewers by involving bodily movement and play. A world’s-first phone app called Track a Raindrop provided user-friendly visualizations of how stormwater travels through the city infrastructure.

Since the 1980s, Mary Miss has been one of the world’s most renowned and celebrated creators of public art and land art. Several of her permanent installations are global landmarks of late-20th century public art and a few, I suspect, have been experienced by more people than any other site-specific modern art installation in the world, due to their locations in central Manhattan.

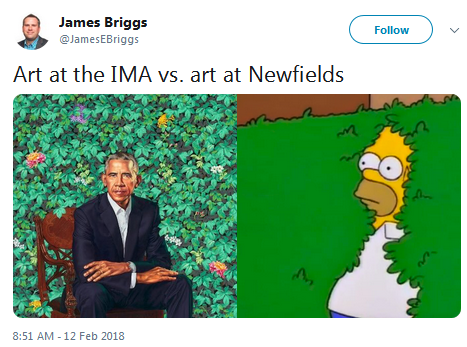

Shockingly, though, hardly any trace of the groundbreaking Indianapolis project has survived online, and it’s looking unlikely that the institution that commissioned it, the former Indianapolis Art Museum, will ever again undertake anything so sophisticated, relevant, and innovative. The article you are reading is essentially the only documentation of FLOW available on online to the general public, the information and photos having been cobbled together from a variety of now-defunct websites. The project was erased from the IMA website after the museum’s highly controversial rebranding last year. The rebranding sparked outrage and withering criticism, with the media and art worlds reporting, accurately, that the museum had “walked away from its mission” and “is arguably not a museum anymore” due to “the greatest travesty in the art world in 2017“, and instead is now more an “Instagram playground” with “fairgrounds-style attractions”.

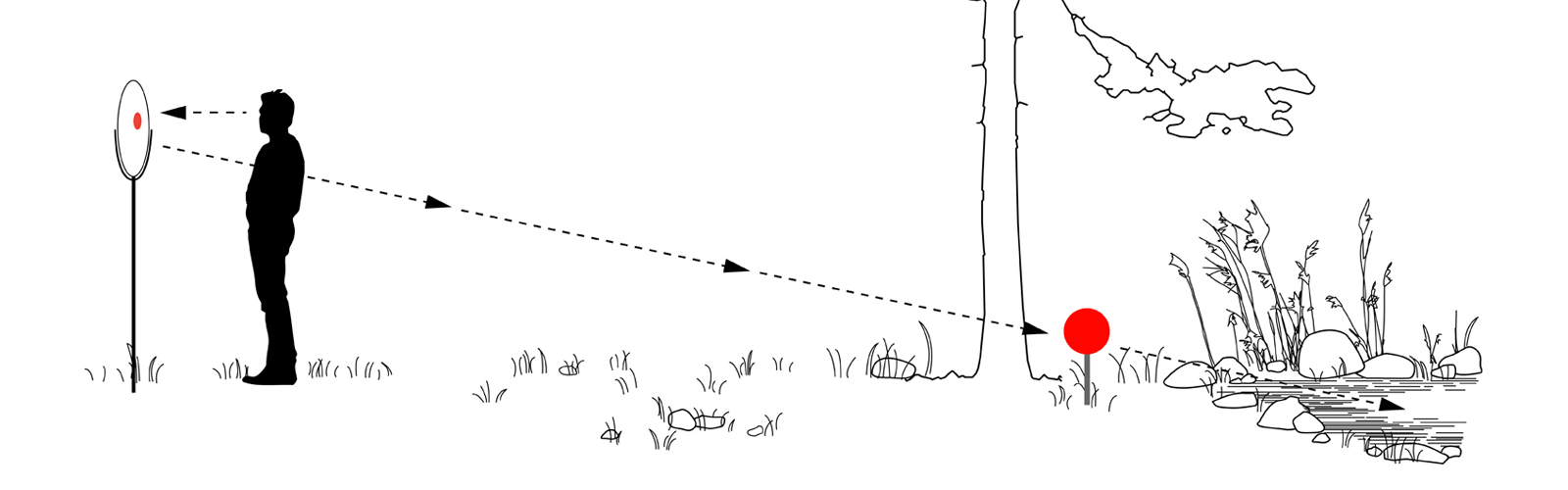

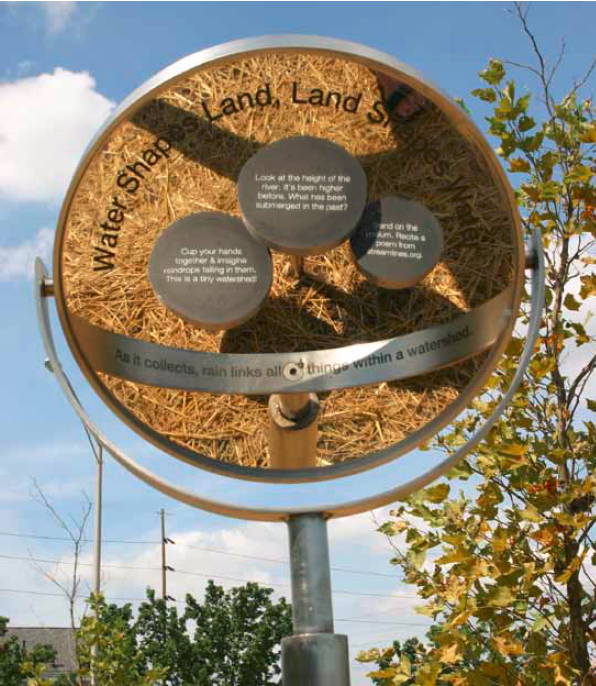

The astonishing and truly unique feature of FLOW was that each giant pin was not necessarily located at the site of the water-related feature it was marking, such as a wetland, dam, or sewer outfall. The pin could be some distance away, up to hundreds of feet. Each feature and pin was paired with a swiveling mirror on a pedestal placed along any of various pathways in parks and riverbanks around the city. Each mirror had a red dot and etched informational text about its respective water feature. It all came together when the viewer turned the mirror so the red dot aligned with the reflection of the distant pin. When they were aligned in the mirror it would appear as though the pin had been placed directly in the wetland or dam itself or alongside it.

The stroke of genius – and this is the whole point of having the mirrors and oversize map pins – was that it allowed for marking features where signs would be impossible to install or too far away from the viewer, such as a publicly inaccessible wetland on the opposite side of the river from a public park. Further, it physically engaged people in getting to know their environment, because you had to stop and turn the mirror and think about what was going on with the big red pin and the water infrastructure.

Mary Miss is known for her innovative blurring of the boundaries between art, landscape architecture, engineering, and education. But this description doesn’t do justice to the physical activity, playfulness, fun and mystery her works inspire. Most people who have ever taken a subway in New York City have seen her work as a large-scale installation is spread throughout one of the largest and busiest stations. The enigmatic bright red metal frames and narrow apertures with half-hidden mirrors and texts throughout the 14th Street subway station are her Framing Union Square (1999-2000). They frame traces of the station from before its modernization, such as mosaics, rivets, and wiring, or mark where elements used to be. She also was the lead artist for the distinctive plaza and promenade at Battery Park City called South Cove (1984), which to this day is said to be the point in Manhattan with the closest pedestrian access to the water and has aged better than many plazas and promenades from that era. For some time her outdoor work has been focused on public engagement and carries the umbrella title of City as Living Laboratory.

FLOW was a collaboration with ecologists at Butler University and Reconnecting Our Waterways, a local environmental organization, and included commissions for dance, music, and poetry works, other public events, and online tools for encouraging connection to and reflection upon local waterways and aquatic ecosystems among the general public.

Equally exciting was the phone application called Track a Raindrop. You clicked on any point on a map of Indianapolis and it showed you the path that every raindrop falling on that point will follow – along the street, into a storm drain if there is one, from there to a stream and eventually into a river and I assume eventually the Gulf of Mexico. I don’t know for sure because the app has disappeared from the internet just like the documentation of the rest of the project so I only know it from a few screenshots I was able to dig up in an archives of deleted websites. Most people don’t realize that every point on the earth is in a watershed and all watersheds drain into rivers. This was a great way to show them.

In 2015, a second project called StreamLines involved fewer installations but had more ways for the public to be active participants, whether individually at the installations or in a program of arts performances.

Each StreamLines site had a platform where a person could stand and look up into a mirror and see text about local water features and systems etched on the mirror and in reflections of structures on the ground, with red balance beams radiating outwards from this point. Other mirrors and signs displayed not just information but prompts for play and physical engagement and exploration: “Listen for birds. When you hear one call, call back.” “Travel between the warmest and coolest spots on this site.” “Discuss: how many times do you cross over a body of water each day?” “Tell a joke from streamlines.org.”

The installations could only remain in place for a year or two because maintenance costs would have been prohibitive. But the lack of enduring and publicly available documentation is a disappointment. It took me weeks of exhaustive digging online just to come up with what you are reading here.

For our non-American readers it’s important to point out this is all in a heavily Republican, anti-environment state. Vice-President Mike Pence was the governor. But like most Republican-dominated states, Indiana has pockets and subpopulations that recognize and respect science, the arts, social justice, and the well-being of future generations and environment they’ll be living in, which why such a project could be realized there. Such a mosaic of diverse co-existing cultures is fairly common in the U.S. and uncommon in, for example, Europe, which tends to self-sort into more homogenous configurations. I mention this to clarify to those unfamiliar with mid-American cities that exciting and inspiring things are not limited to the liberal coasts and can be found across the country, under the radar.

That leads us to the heartbreaking story of the Instagramification of the Indianapolis Art Museum, arguably the greatest fall of an art museum in American history. Once one of the country’s finest and most respected museums, shortly after FLOW it all but abandoned its mission and became a tawdry, pandering presenter of events such as those globally traveling exhibitions of big-screen videos of Monet, and a marketing fig-leaf for global corporations.

The decline is striking. The IMA has the eighth largest endowment and eighth largest main building among U.S. museums even though Indianapolis is the 33rd largest city. It gets more visitors than the Frick in New York or the Cleveland Art Museum which has twice the endowment and a global reputation (although the IMA was excellent it wasn’t quite at the level of Cleveland, which routinely loans works to prestigious European exhibitions.)

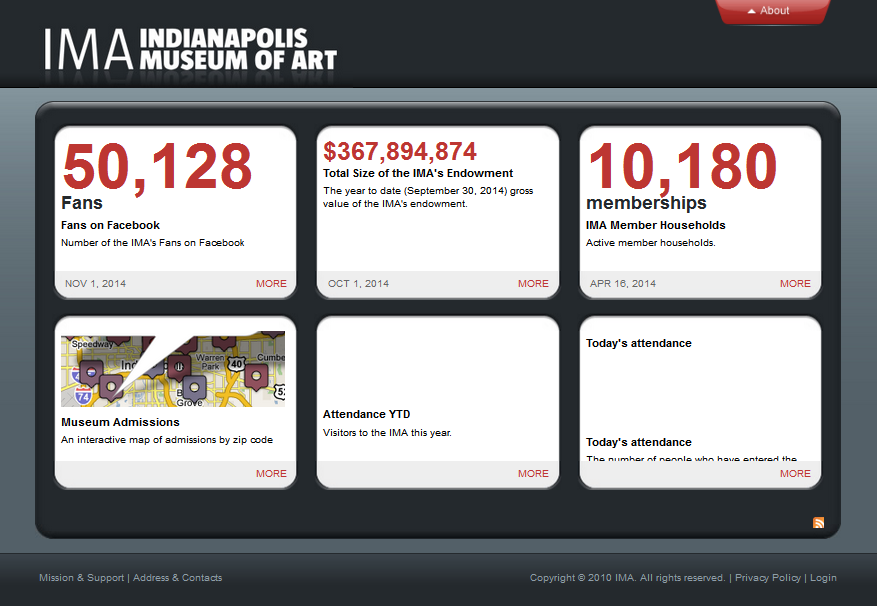

The IMA is located adjacent to the estate of its primary benefactors, the Lilly pharmaceutical family, who donated the estate’s house and grounds, now registered landmarks, to the museum in 1966. In 2002 the same Lilly heiress gave $200 million to the Poetry Foundation (yes, $200 million). The museum once had a reputation for innovative, challenging exhibits and early engagement with the digital realm such as its revolutionary “Dashboard” website, since erased like the FLOW documentation, that provided user-friendly, easily accessible data on behind-the-scenes aspects of the museum such as size of the endowment and numbers of visitors with a map showing their home zip codes. It followed a rich tradition of art that illuminates the social, political and economic systems of the art world, first pioneered by figures such as Hans Haacke, whose solo exhibition at the Guggenheim was so critical of large corporations that they forced its cancellation at the last minute.

But after an over-ambitious expansion program in the early 2000s led to financial troubles – attendance has stalled at half the number that was predicted – the museum fired its director and hired a new one whose massive restructuring and rebranding scandalized the art world. Around 2012, twenty-nine staff positions were eliminated, a staggering number for a museum, including seven out of the museum’s twelve curators and the director of publications. The museum refused to say which positions were gone. Admission went from free to eighteen dollars, the internship program was eliminated and the library ceased having regular hours and is now open only by appointment. An exhibit of cars was held. And that was before the travesty really got underway.

It seems the museum solved the worst of its financial issues shortly after these dramatic changes, but still the director and trustees went farther and carried out a tectonic shift in the museum’s identity and its role in the city’s and the country’s culture. In the restructuring, the name Indianapolis Art Museum was eliminated and the museum repositioned as just one amenity among many in a multipurpose site christened Newfields, which encompasses several entities that are adjacent to the museum and institutionally linked to it, either formally or informally: a critically acclaimed 100 acre sculpture park opened in 2010, a beer garden, and Oldfields, the aforementioned Lilly house and gardens (hence the neologism), and more. The first time I viewed the Newfields website, before I knew any of this, I was confused because my searches for the Indianapolis Art Museum kept ending up at what I thought was an upscale resort or shopping mall that was trying to be classy by offering some sort of art tours. After extensive digging it dawned on me that this was the husk of the Indianapolis Art Museum and it had been renamed Newfields – but don’t try to find this explained at the Newfields website because they don’t mention their former name.

Now, the museum is lost in an avalanche of lowest-common-denominator, pandering, Instagram-targeted “experiences”. This is where art, culture and thought itself go to die in a pit of the most vulgar, focus-grouped, algorithm-derived marketing-speak that late capitalism has to offer. The website overflows with patronizing, hucksterish commands to “Shop & Eat” and “Do & See”. Where once there were exhibitions such as “Roman Art from the Louvre”, now there is yoga – directly in the galleries, with no apparent concern over the effects of sweat on priceless art treasures – and Saturday morning “cereal and a movie”. The website is a relentless barrage of phony, shrill and desperate-sounding exhortations to “explore” and “experience”. “A place for kite-flying, cloud-gazing, memory-making, new-idea-having”. “A mansion to stage unforgettable events, restaurants for relaxing, bars for microbrews and friendships”, which can describe more or less any place anywhere on the planet and certainly has no detectable relevance to art. The flagship even of the year is Christmas lights. But renamed Instagramspeak to “Winterlights”: “see the lights dance again as you amble side by side with family and friends”, instructs the website, which seems to be intended for people who need someone to explain the tme how to look at Christmas lights.

“Cheap midwestern boardwalk” as City Lab put it (when City Lab was still at the somewhat respected Atlantic, before billionaire Michael Bloomberg bought City Lab in 2019 in an ironic parallel of the Newfields debacle), accurate in mood if not geography, given that only seashores have boardwalks. The director was quoted as saying he can’t understand why the museum shouldn’t get as many visitors as the city’s runaway successful children’s museum, which sounds like something from the Fox News School of Art Criticism. He started a Facebook page just for his 20-room mansion where he shared his redecorating plans and passed judgement on the caterers of his galas. The media and art world howled, mocked, and heaped deserved scorn on the sad and self-inflicted degradation.

Naturally the art is still there in the museum. There are collection tours, though they are jumbled haphazardly among the listings with Instagram-style photos of Christmas wreath making and the yoga women. There’s a George Platt Lynes exhibit, which seems to have the challenging spirit of the “old” museum, raising the suspicion that it was planned before the museum’s suicide.

For now, it still has its revolutionary, first-ever-worldwide online database of deaccessioned works where you can see which artworks the museum has sold off from its collection and when and in most cases why. This is a crucially important service and it is a travesty that few if any other museums provide it. Deaccessioning is extremely controversial and secretive in the museum world, (just plain prohibited by law in France and Germany, I am told). The reason is that it can turn museums into profit-driven speculators and can send the message to donors that the museum could someday sell off their donations. Indianapolis’ great step towards transparency, begun in the 2000s was a bold and rare move to show they only deaccession for very good reason, but in the museum’s new orientation it seems unlikely to survive at all.

Good luck finding the database, anyway, buried as it is in deep in the website, many labyrinthine clicks behind the yoga classes. I never would have known it’s there if I hadn’t seen it mentioned in negative criticism of the museum’s rebranding, as an example of the kinds of things the IMA – pardon, Newfields – doesn’t do any more. Mary Miss and the FLOW project have been scrubbed from the site entirely.

In a talk about FLOW, Miss said one of her inspirations was the Borges’ story about the life-sized map, and elsewhere in the talk she discusses aquatic ecosystems. The contrast between Miss’ thoughtfulness and creativity, and the tawdry gimmicks such as Winterlights® is staggering. I get it, the museum needs to take advantage of the gardens and parks and other sights at the location in order to drawn in visitors. But as the City Lab writer put it, “where the Indianapolis Museum of Art strove to challenge its audience, Newfields pats their heads.”

The FLOW website is archived here.

Image credits: Mary Miss / CALL, Indianapolis Museum of Art