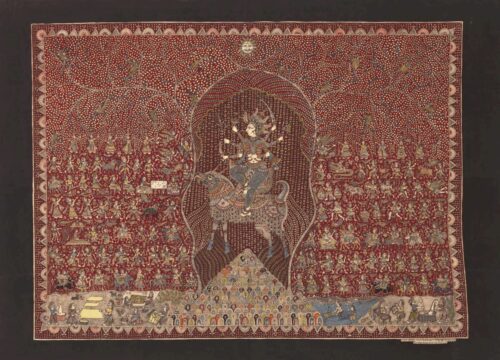

For nearly two millienia, India was the only place where people had figured out how to dye or print in a range of colors on cotton. Before modern industrial chemicals, getting just about any color – apart from indigo and a couple others – to stick to cotton fabric involved complicated, labor-intensive methods and obscure plant extracts that no one else had discovered. As early as 70 A.D., Pliny was marveling in over India’s colored cottons; the British couldn’t dye cotton until they learned India’s methods in the mid-1700s through their colonial trade. Until then, India was more or less the only supplier of colorful printed cottons, or chintz – a Hindi word – not just to Europe but also throughout Asia and they didn’t simply export their own designs but instead tailored them to each region’s local traditions. An exhibition at the St. Louis Art Museum entitled Global Threads: The Art and Fashion of Indian Chintz tells the story.

Click to enlarge and page through each set

Chintzy means cheap although chintz fabric is expensive – why is that?

Have you ever wondered why chintz is an expensive fabric for upholstery but chintzy means cheap and tacky? The origin is the Hindi word chit or chimt which means variegated and the English borrowed it to refer to high-quality colorful printed cottons which were widely popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries but had to be imported from India until British explorers and colonists learned the methods. With industrialization in the nineteenth century the popularity of chintz grew and cheap, low-quality imitations first became available. It was at this time, in 1851, that George Eliot mentioned in a letter that some fabric she was thinking of buying looked “chintzy”, indicating that people with refined tastes and style were avoiding these newer cheap copies that the lower classes could afford, and that’s the first known appearance of the word.

Designs for European tastes

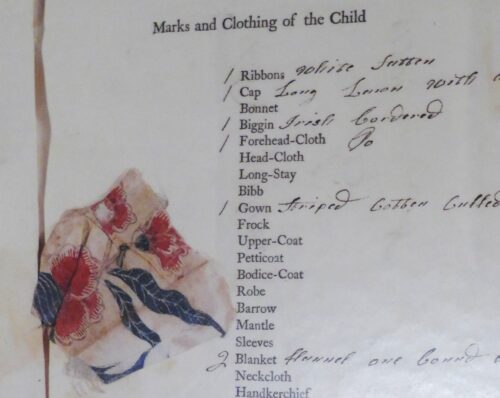

When impoverished mothers left children at Foundling Hospitals in England, they often left a swatch of Indian chintz to later prove kinship, as in this page from a hospital “billet book” from 1759.

Clothing exported from India in the 1700s to England (left, man’s dressing gown) and a remote part of Holland (right, woman’s jacket) where chintz was especially popular.

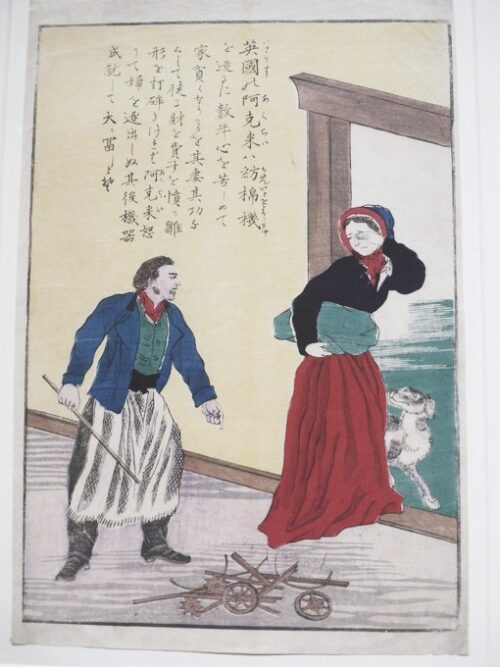

Indian chintz in Japan

Lives of Great People of the Occident was a series of woodblock prints published by the Japanese Ministry of Education in 1873 for teaching about European inventors. This one depicts Sir Richard Arkwright, inventor of a revolutionary machine for carding cotton, throwing his wife out of the house because she had wrecked one of his prototypes out of anger at him for spending too much time on what appeared to be useless pursuits.

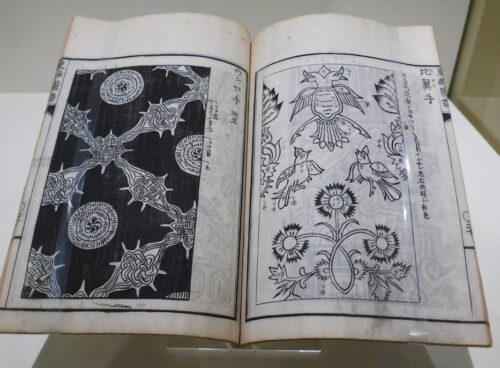

Illustrated Manual of Chintz (1785), published in Japan for collectors of Indian chintz

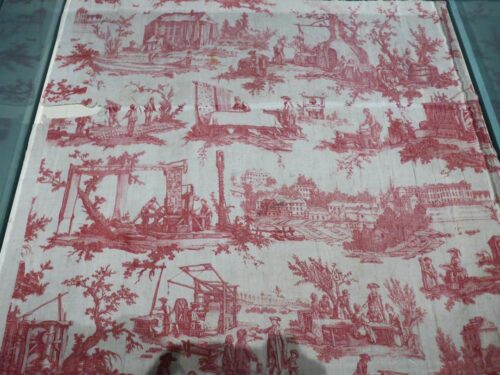

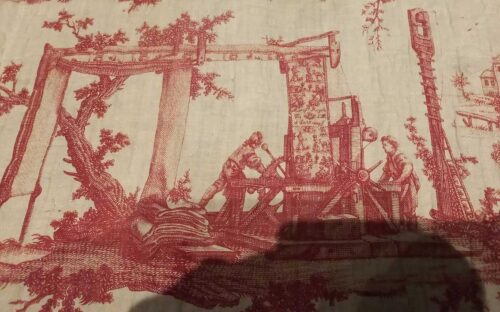

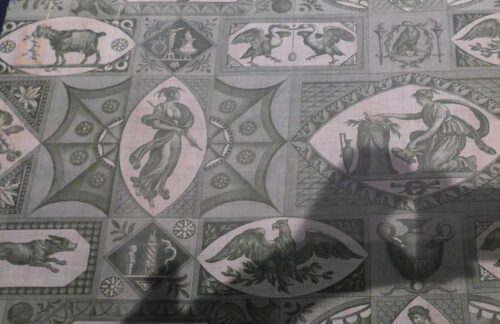

French toiles

Toile (cloth or canvas), or toile de Jouy, means chintz printed with scenes of people, landscapes or animals that became popular in the 18th century. One of France’s centers for it was the town of Jouy. The red one (1783) depicts fifteen or so of the many laborious steps in making printed cottons. The green one (1803) is one of the first European textiles ever printed in green which is an especially difficult color to achieve.

Cotton is incredibly difficult to dye

Cotton is very resistant to dying and printing, and apart from that it doesn’t grow well in Europe so it was seldom if ever used for clothes until the sixteenth or seventeenth century. Before that nearly all fabric in Europe was made of linen or wool, along with silk for the rich. As early as 70 A.D. Pliny commented on the complicated and mysterious procedures that were known to exist in Asia for dying cotton, and which hardly changed until the development of industrial chemicals in the late nineteenth century.

Without modern chemcials you can’t just dye cotton as we think of dying. You have to dye it with a special dye that will not have the color you want until you apply a fixative called a mordant which transforms the dye into the color you want and fixes it to the fabric. So for example to make a pattern of red flowers you print the flowers using wood blocks and a dye that doesn’t appear red; let’s say it looks blue. Let it dry, then place the whole fabric in a mordant bath. The blue flowers will turn red and then you wash out all the mordant.

Each color requires a different mordant, and this simplified description has omitted many steps, not the least of which is drying the fabric in the sun for days between each one. A design with five or six colors can involve thirty steps and a couple months of work. Modern chemicals and technology have eliminated all this effort and nowadays just a few artisans carry on the traditional pre-industrial methods.